April is Stress Awareness Month, so let’s learn more about the stress hormone known as cortisol!

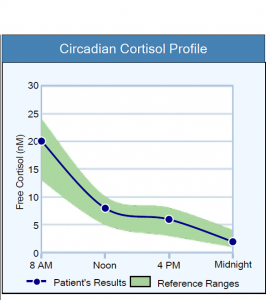

While cortisol is known as the stress hormone, it is crucial for the optimal function of the body every day. In healthy individuals, cortisol levels naturally shift throughout the day in a pattern known as a diurnal rhythm. A diurnal rhythm is a circadian rhythm that is repeated every 24 hours and synchronized with the day/night cycle.1 The presence of “stress” or certain medical conditions can affect cortisol levels and disrupt a healthy diurnal rhythm.2

Here is an example of a healthy diurnal rhythm:

We often think of “stress” as the emotional stress felt while stuck in traffic or overwhelmed at work. But, stress encompasses anything that increases the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which controls the release of cortisol.2,3 Pain, prolonged fasting, negative thinking, low blood pressure, acute and chronic infections, low blood oxygen, food sensitivities, intense exercise, low blood sugar, and other circumstances are also interpreted as stress by the body.2

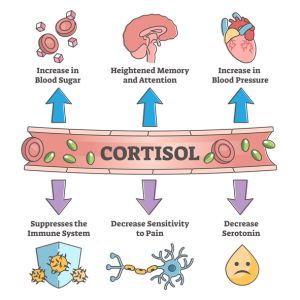

Cortisol directly impacts most organs and cells in the body and the activity of the immune, cardiovascular, respiratory, reproductive, musculoskeletal, integumentary, gastrointestinal, and nervous systems. Therefore, learning more about the stress hormone cortisol and testing saliva cortisol levels in your patients could be the next important step on their path to wellness.3

What is cortisol?

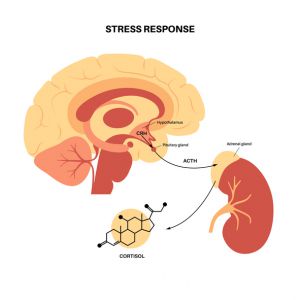

Cortisol is a steroid hormone that is made by the adrenal glands. When stress occurs, the hypothalamus increases the production of corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) to stimulate the release of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland. The ACTH then stimulates the release of cortisol from the adrenal glands. The subsequent increase in the cortisol level improves the ability to respond to stressors while maintaining balance or homeostasis, which is why it is known as the stress hormone.2

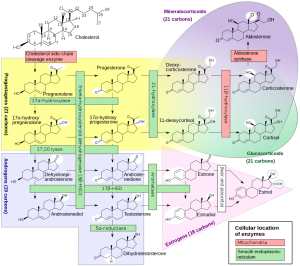

Cortisol is produced from cholesterol, the precursor for all steroid hormones, including testosterone and progesterone. To produce cortisol, cholesterol needs to be shuttled into the mitochondria in the cells in the adrenal glands. Once in the mitochondria, the cholesterol is converted to the hormone pregnenolone.4

The pregnenolone is then converted to progesterone, and the progesterone can be converted to 17-OH progesterone, which is pronounced as “17-hydroxy-progesterone.” Finally, enzymes convert the 17-OH progesterone (17OHP) to cortisol in the adrenal glands.4

Here is a picture of the steroid hormone production (steroidogenesis) pathways:

It is possible to have a high cholesterol level (hypercholesterolemia) and a low cortisol level, which could be caused by mitochondrial dysfunction. Researchers have confirmed that mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with hypercholesterolemia, and steroid hormone production occurs in the mitochondria.5 Low levels of other hormones, including testosterone, could also be associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and high cholesterol levels.

Since cholesterol is the precursor for cortisol, low cholesterol levels (less than 150 mg/dL) can also contribute to low cortisol levels.6

After cortisol is produced and released by the adrenal glands, it binds to carrier proteins in the blood, such as corticosteroid-binding globulin (CBG) and albumin. Approximately 95% of the circulating cortisol is bound to CBG in the blood, but this percentage can vary. Cortisol must separate, or dissociate, from CBG before it can enter a cell and have an effect.2 This is one reason saliva hormone testing is better than a blood test; saliva offers an opportunity to directly measure the free, bioactive cortisol level.

After the cortisol dissociates from CBG in the blood, it crosses cell membranes throughout the body because the cell membranes are composed of fatty phospholipid bilayers, and cortisol is fat-soluble. When cortisol enters the cell, it binds to a glucocorticoid receptor. Then, the cortisol-receptor complex enters the nucleus of the cell to affect Gene expression as needed to support the body during times of physical, mental, emotional, and other types of stress.3

Abnormal cortisol levels can be detrimental to the health of your patients, whether the cortisol levels are too high, too low, or released in a misaligned diurnal rhythm.3,7

What does cortisol do?

Overall, cortisol helps maintain balance, or homeostasis, in your body during times of stress. Pain, low blood glucose levels, and intense exercise are all types of stress that could induce the release of extra cortisol.2

According to a clinical trial by Goodin et al., increased pain levels directly correlate with increased cortisol levels.8

When pain is experienced, it is usually a cue to get away from the cause of the pain, whether it is a hot stove or a lion attack. When attacked by a lion, or other threat, one needs to be able to fight the lion and run away. The stress response and the release of extra cortisol will help one fight, escape, and survive a lion attack (or other causes of pain). The extra cortisol helps maintain homeostasis in the body while responding to (or escaping from) the stressor.

The increased cortisol levels seen in the pain study were also associated with lower levels of inflammation, specifically the soluble tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor II response.8 In general, cortisol and other glucocorticoids are considered anti-inflammatory, but because life is often complicated, the effects of cortisol on the immune system are not black & white.9

Cortisol can also induce inflammatory effects at times. Research shows the initial low levels of cortisol during a stress response have an inflammatory effect, while the higher levels of cortisol that are associated with a more prolonged stress response are anti-inflammatory.9

With regard to homeostasis or balance, scientists hypothesize that the anti-inflammatory effects of higher cortisol levels help prevent excessive destruction from the initially elevated levels of inflammation present during a stress response or trauma. The anti-inflammatory activity of higher cortisol levels also appears to prevent the development of autoimmune diseases.9

Glucocorticoids, including cortisol, can induce the cell death of pro-inflammatory T cells, suppress B cell antibody production, reduce neutrophil migration, and affect the immune system in other ways to reduce inflammation.3,8

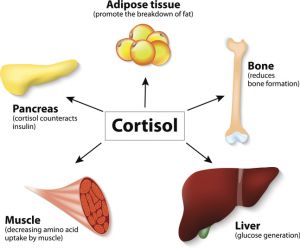

Cortisol also increases the amount of glucose and other energy sources present in the blood as part of the stress response.2 Since the brain prefers glucose as an energy source, the more glucose available to the brain during a stressful event, such as a lion attack, the better!10 In the liver, cortisol increases gluconeogenesis, which is the production of glucose. Cortisol also enhances the activity of other hormones that increase the blood glucose level, including glucagon, epinephrine, and other catecholamines.3 This is how the release of extra cortisol helps re-balance a low blood glucose level and how the stress response provides the energy needed to respond to a stressful situation.

Cortisol also stimulates muscle cells to increase protein degradation, increasing the level of amino acid building blocks available in the blood so the liver can increase glucose production. Yes, the liver can produce sugar from amino acids! In fat (adipose) tissue, cortisol increases lipolysis, or the breakdown of fat, to provide another source of immediate energy for the body.3

Cortisol has many valuable effects on the body during intense exercise, which is a beneficial stress. As discussed above, cortisol increases the availability of metabolic nutrients, including fatty acids, amino acids, and glucose, for the energy needs of muscles and other tissues during exercise.3,11

Cortisol helps maintain normal blood vessel integrity and responsiveness during exercise. Cortisol also prevents an overreaction of the immune system to repeated exercise-induced muscle damage and reduces inflammation to hasten recovery. And, even though exercise is a stress on the body, it is beneficial stress because, over time, regular physical exercise leads to less stress reactivity and enhanced stress recovery from emotional stress and other types of stress, compared to untrained subjects.11

Underlying Causes and Symptoms of Abnormal Cortisol Levels

While the stress response, including the release of extra cortisol, is beneficial and helps one respond to and re-balance during stress, an abnormal cortisol level due to too much long-term stress, an underlying medical condition, or other cause can be harmful.

High cortisol levels can be caused by Cushing syndrome, an acute stress response, the early stages of chronic stress, major depressive disorder (MDD), and other conditions.12,13

Chronically elevated cortisol levels are associated with many concerning health issues, including weight gain and obesity; muscle loss; high blood sugar levels and diabetes; insulin resistance; chronic infections; high blood pressure; increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease; loss of bone mineral density; memory loss; insomnia and other sleep issues; fragile or thinning skin; mood disorders, including anxiety and bipolar disorder; and abnormal cholesterol levels.12,14

Low cortisol levels can also be harmful.

A low cortisol level could be caused by Addison’s disease; congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH); non-classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia (NCCAH); Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD); long-term chronic stress or adrenal fatigue; long COVID and other chronic infections; mitochondrial dysfunction; current or past history of prescription corticosteroid medication(s); low cholesterol levels due to malabsorption syndromes, the use of statin medications, liver dysfunction, or other causes; and other medical conditions.13,15-22

Chronic hypocortisolism can be an underlying cause of or contributing factor to many health concerns, including chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), hypotension, hypoglycemia, weight loss, burnout with physical symptoms, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, flexion contracture, fibromyalgia, and other chronic pain syndromes.23-26

Even if the total amount of cortisol released by the adrenal glands in 24 hours is normal, an abnormal diurnal rhythm is associated with suboptimal health. Ideally, cortisol production should be at its highest just after awakening in the morning and lowest at night before bedtime. Some patients have high cortisol levels at night and low cortisol levels in the morning. This abnormal rhythm, or a circadian misalignment, is associated with daytime fatigue, insomnia, obesity, and many other health concerns.7,27

If your patients have any of the symptoms or health conditions mentioned above, such as fatigue, insomnia, long COVID, anxiety, high cholesterol, depression, or high blood pressure, consider checking their salivary cortisol levels soon.

To assess the health of the daily cortisol diurnal rhythm in your patients, order our popular Adrenal Stress Index panel. An overview of our Adrenal Stress Index panel is available HERE.

To place a test order, click here. As a reminder, DiagnosTechs can drop ship test kits directly to your patients. You may select this option at the top of the order form.

Please visit our Provider Tools page for further information about test selection, test interpretation, and more!

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

THE BENEFITS OF SALIVA HORMONE TESTING

If you could choose, would you rather spit into a tube or have a needle jabbed into your arm to measure your hormone levels? We suspect you would rather not get stuck with a needle, and you do have a choice! Saliva hormone testing offers many benefits, including painless collection in the comfort of your home at any time. Saliva hormone tests can help determine the underlying cause(s) of PMS, insomnia, anxiety, fatigue, infertility, migraines, weight gain, hot flashes, hair loss, and many other health concerns.

Do you and your patients enjoy watching college basketball games during March Madness every year? We do! Perhaps this year, you could also participate in some Magnesium Madness! What is so mad about magnesium? Well, research shows that at least 48% but up to 75% of the population does not consume enough of this crucial mineral daily. Madness!

In honor of American Heart Month, we are sharing information about the beneficial effects of bioflavonoids on your cardiovascular system. Heart disease is the number one cause of death worldwide, so consider taking better care of your heart by reading our blog and increasing your intake of heart-healthy bioflavonoids.

SYNERGISTIC NUTRIENTS FOR ADRENAL SUPPORT

We often think of supplements as vitamins and minerals that need to be taken only as needed for potential nutrient deficiencies or inadequacies. However, nutritional supplements offer much more and can manifest powerful synergistic benefits that go far beyond simply replacing the vitamins and minerals missing from your diet.

RELAXATION TECHNIQUES FOR STRESS RELIEF

For many of us, relaxation means flopping on the couch and zoning out in front of the TV at the end of a stressful day. But this does little to reduce the damaging effects of stress. Rather, you need to activate your body’s natural relaxation response, a state of deep rest that puts the brakes on stress, slows your breathing and heart rate, lowers your blood pressure, and brings your body and mind back into balance.

References

- Hedge A. Biological Rhythms – Cornell University. Cornell University Ergonomics Web. https://ergo.human.cornell.edu/studentdownloads/DEA3250pdfs/biorhythms.pdf. Published August 2013. Accessed February 13, 2023.

- Raff H, Carroll T. Cushing’s syndrome: from physiological principles to diagnosis and clinical care. J Physiol. 2015;593(3):493-506. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2014.282871

- Thau L, Gandhi J, Sharma S. Physiology, cortisol – statpearls – NCBI bookshelf. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538239/. Published August 29, 2022. Accessed February 9, 2023.

- Schiffer L, Barnard L, Baranowski ES, et al. Human steroid biosynthesis, metabolism and excretion are differentially reflected by serum and urine steroid metabolomes: A comprehensive review. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;194:105439. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.105439

- Vercesi AE, Castilho RF, Kowaltowski AJ, Oliveira HC. Mitochondrial energy metabolism and redox state in dyslipidemias. IUBMB Life. 2007;59(4-5):263-268. doi:10.1080/15216540601178091

- Manosroi W, Phimphilai M, Khorana J, et al. Predictive Factors of Adrenal Insufficiency in Outpatients with Indeterminate Serum Cortisol Levels: A Retrospective Study. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56(1):23. doi:10.3390/medicina56010023

- Morris CJ, Purvis TE, Mistretta J, Scheer FA. Effects of the Internal Circadian System and Circadian Misalignment on Glucose Tolerance in Chronic Shift Workers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(3):1066-1074. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-3924

- Goodin BR, Quinn NB, King CD, et al. Salivary cortisol and soluble tumor necrosis factor-α receptor II responses to multiple experimental modalities of acute pain. Psychophysiology. 2012;49(1):118-127. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01280.x

- Sorrells SF, Sapolsky RM. An inflammatory review of glucocorticoid actions in the CNS. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(3):259-272. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2006.11.006

- Mergenthaler P, Lindauer U, Dienel GA, Meisel A. Sugar for the brain: the role of glucose in physiological and pathological brain function. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36(10):587-597. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2013.07.001

- Duclos M, Tabarin A. Exercise and the Hypothalamo-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. Front Horm Res. 2016;47:12-26. doi:10.1159/000445149

- Findling J, Munir K, Agrawal N, Fish S. Cushing’s syndrome and Cushing disease. Endocrine Society. https://www.endocrine.org/patient-engagement/endocrine-library/cushings-syndrome-and-cushing-disease. Published March 31, 2022. Accessed February 13, 2023.

- Almeida FB, Pinna G, Barros HMT. The Role of HPA Axis and Allopregnanolone on the Neurobiology of Major Depressive Disorders and PTSD. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(11):5495. doi:10.3390/ijms22115495

- Favero V, Cremaschi A, Parazzoli C, et al. Pathophysiology of Mild Hypercortisolism: From the Bench to the Bedside. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2):673. doi:10.3390/ijms23020673

- Adriaansen BPH, Schröder MAM, Span PN, et al. Challenges in treatment of patients with non-classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1064024. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.1064024

- Kwda A, Gldc P, Baui B, et al. Effect of long term inhaled corticosteroid therapy on adrenal suppression, growth and bone health in children with asthma. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):411. doi:10.1186/s12887-019-1760-8

- Mosca AM, Barbosa M, Araújo R, Santos MJ. Addison’s Disease: A Diagnosis Easy to Overlook. Cureus. 2021;13(2):e13364. doi:10.7759/cureus.13364

- Corkery-Hayward M, Metherell LA. Adrenal Dysfunction in Mitochondrial Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(2):1126. doi:10.3390/ijms24021126

- London E, Tatsi C, Soldin SJ, et al. Acute Statin Administration Reduces Levels of Steroid Hormone Precursors. Horm Metab Res. 2020;52(10):742-746. doi:10.1055/a-1099-9556

- Cachefo A, Boucher P, Dusserre E, et al. Stimulation of cholesterol synthesis and hepatic lipogenesis in patients with severe malabsorption. J Lipid Res. 2003;44(7):1349-1354. doi:10.1194/jlr.M300030-JLR200

- Salzano C, Saracino G, Cardillo G. Possible Adrenal Involvement in Long COVID Syndrome. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(10):1087. doi:10.3390/medicina57101087

- Kirschbaum C. What to do now that hypocortisol appears to be a predominant sign of long COVID?. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2022;145:105919. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2022.105919

- Younes N, Bourdeau I, Lacroix A. Latent Adrenal Insufficiency: From Concept to Diagnosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:720769. doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.720769

- Heim C, Ehlert U, Hellhammer DH. The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of stress-related bodily disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25(1):1-35. doi:10.1016/s0306-4530(99)00035-9

- Agorastos A, Chrousos GP. The neuroendocrinology of stress: the stress-related continuum of chronic disease development. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(1):502-513. doi:10.1038/s41380-021-01224-9

- Tanaka T, Terada N, Fujikawa Y, Fujimoto T. Treatable Bedridden Elderly -Recovery from Flexion Contracture after Cortisol Replacement in a Patient with Isolated Adrenocorticotropic Hormone Deficiency. Intern Med. 2016;55(20):2975-2978. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.55.6932

- Kelly RM, Healy U, Sreenan S, et al. Clocks in the clinic: circadian rhythms in health and disease. Postgrad Med J. 2018;94(1117):653-658. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2018-135719

Source:

Source: